Amid intense conflict with the United States and Israel, speculation has mounted over the fate of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is reportedly in hiding due to fears of assassination. This follows a dramatic escalation in the region, including US airstrikes on key Iranian nuclear facilities and Iran’s retaliatory missile attacks on US bases.

Here’s what could happen if Khamenei is removed from power or dies during this period of heightened volatility:

1. Power Vacuum and Temporary Succession

If Khamenei dies or is removed, the first step would be the formation of a Leadership Council or the swift appointment of an interim Supreme Leader. Iran’s Assembly of Experts — an elected body of Islamic scholars — is constitutionally responsible for choosing the next Supreme Leader.

However, in practice, powerful clerics and figures in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are likely to exert enormous influence on this decision, especially during a national crisis.

2. Potential Candidates for Leadership

Some of the frequently mentioned potential successors include:

- Ebrahim Raisi (President of Iran and a key Khamenei ally, though his health and political standing may be under scrutiny)

- Mojtaba Khamenei, the Supreme Leader’s son, a powerful cleric with reported IRGC backing

- Other senior clerics close to the conservative religious establishment

The selection process could become contested, especially if factions within the regime — reformists vs hardliners vs the military — view it as a chance to consolidate power.

3. Increased Risk of Internal Instability

Khamenei’s death or removal during an international military crisis could trigger:

- Mass protests or power struggles within Iran, particularly if succession is seen as illegitimate or overly influenced by the IRGC.

- Dissent from reformist groups or ethnic minorities, who may see the moment as an opportunity to challenge the regime’s authoritarian structure.

- Infighting within the ruling elite, especially between traditional clerics and military commanders.

4. IRGC Consolidation of Power

The IRGC, already a dominant force in Iran’s politics and economy, may take the opportunity to tighten its grip. In a worst-case scenario, Iran could see a shift from a theocratic model to an overt military-led state, effectively sidelining civilian governance.

This would likely harden Iran’s stance against the US and Israel, escalate regional conflicts, and increase the risk of a full-scale war or proxy escalation in places like Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq.

5. Regional and Global Implications

- The U.S. and Israel may be wary of a power vacuum in a nuclear-ambitious state, prompting tighter sanctions, increased surveillance, or even direct military interventions to prevent proliferation or retaliation.

- Russia and China, Iran’s strategic allies, could attempt to mediate or bolster the new regime for geopolitical advantage.

- Neighboring Gulf States would likely increase their defense readiness, anticipating either instability or Iranian aggression.

.jpg)

Donald Trump ordered the US military to attack Iran over the weekend (Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

In Iran’s system, the Supreme Leader holds more power than the president, who carries out the Supreme Leader’s orders rather than setting policy independently.

Unlike presidents elsewhere, they do not have ultimate authority over the government; that power rests entirely with the Supreme Leader.

What happens when Iran’s leader dies or is deposed?

According to Iran’s constitution, a group of 88 senior clerics who make up the Assembly of Experts are tasked with picking a new Supreme Leader.

This assembly is vetted by another clerical body, then approved via election, explains the Atlantic Council.

It’s quite similar to the Conclave cardinals electing a new Pope in the Catholic Church.

However, these things don’t often run to plan.

Over its 43-year history, Iran has changed Supreme Leaders only once, after Ayatollah Khomeini died in 1989.

Khomeini had first picked Ayatollah Montazeri to replace him, but then removed him when Montazeri publicly criticized an earlier mass execution of political prisoners. So, no new successor was named before Khomeini’s death.

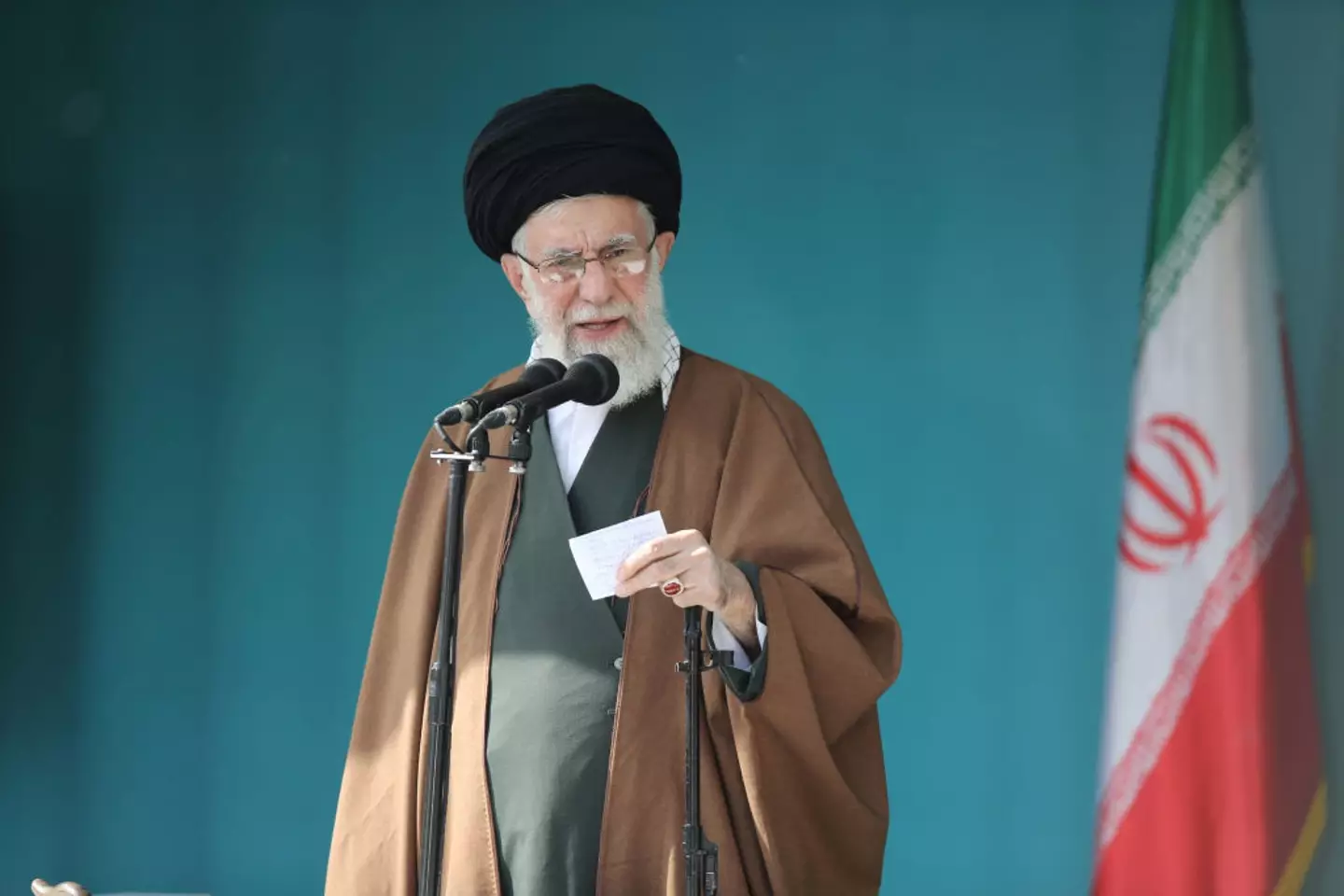

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei (Sadegh Nikgostar ATPImages/Getty Images)

When Khomeini died, the Assembly of Experts chose President Ali Khamenei, then a mid-level cleric, to take over.

Iran’s constitution was changed so that someone with a lower religious rank could be the leader, and the prime minister’s job was abolished while the presidency gained more power.

Khamenei resigned as president and was approved as Supreme Leader; Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani then became president twice.

Over time, Khamenei, now promoted to ayatollah, outgrew Rafsanjani’s influence by building a strong alliance with the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC).

Today, the IRGC wields massive economic and security power, and likely holds more sway over choosing the next Supreme Leader than any other group.

Will Iran get a new leader according to its laws?

The New York Times has said that Khamenei has named three possible successors, which have yet to be reported.

Ray Takeyh, Hasib J. Sabbagh, Senior Fellow for Middle East Studies, Council on Foreign Relations, spoke at a media briefing on June 13.

He explained how, should foreign strikes damage Iran’s leadership but avoid mass civilian casualties, public opinion might not turn solidly against those strikes.

He has served as the second Supreme Leader of Iran since 1989 (Iranian Leader’s Press Office – Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Why? Well, many people already distrust the government, largely due to their prioritization of building nuclear weapons.

And while a succession plan is unclear, nobody knows who would replace Khamenei, or whether that person could unite Iran’s ruling factions.

Takeyh said: “Now, the question is, can the society overwhelm the state even in its weakened condition? I don’t have the answer to that question.”

In part, he continued: “They may arrive at the same conclusion as the past, that their economic vulnerabilities and other sort of ability of the Israelis and Americans to exact an economic price upon them still militates that restraint.

“But again, I don’t think they know the answer to that question. And I certainly don’t know the answer to that question, because everybody’s trying to sort this out in real time.

“Ali Khamenei is still – within the regime, at least, his ability to impose order is there. Now whether he’ll have a successor at that time with a similar degree of authority, I don’t think so, in the short term.

“Which means other centers of power will have their own prerogatives. And the regime will be much more chaotic in its decision making.”